“Silent Stream” – Rachel Carson knew how important beavers & willows are to biodiverse ecosystems.

More than 60 years have passed since Rachel Carson wrote the influential book Silent Spring. Her goal was to inform readers of environmental damage that results from the indiscriminate use of pesticides & herbicides. Promotion & use of these newly discovered chemicals was common practice in her day.

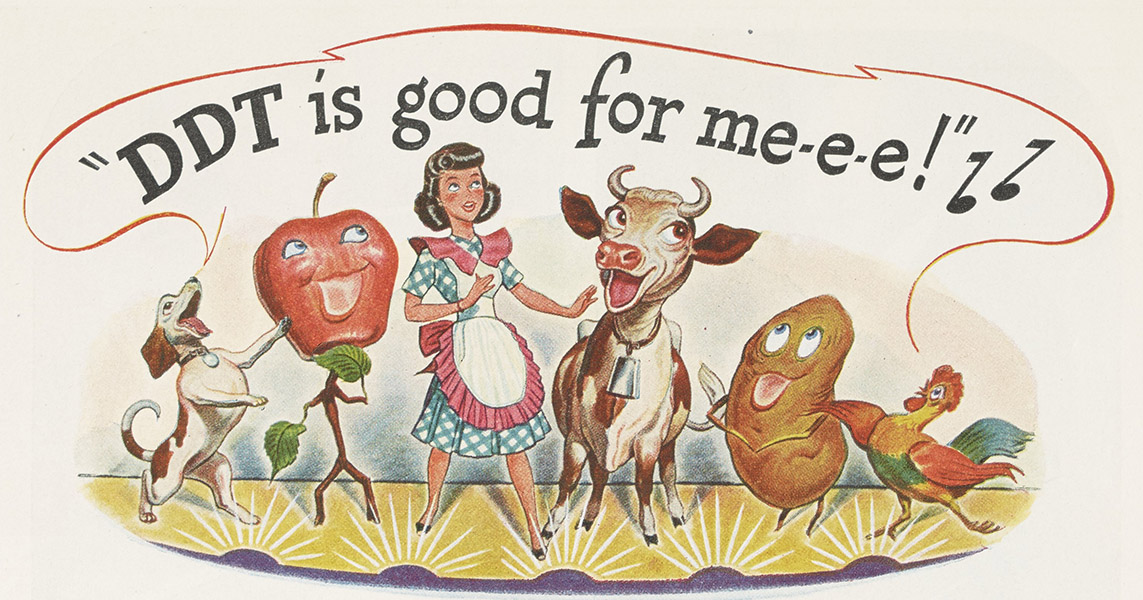

Ad promoting Pennsalt DDT products that appeared in Time Magazine, June 30, 1947

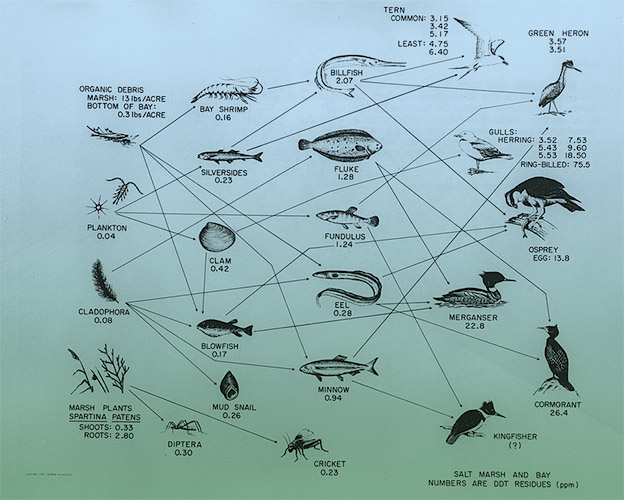

Those familiar with Silent Spring may tend to think of the case of the near extinction of the Bald Eagle due to the pesticide DDT. Ten years after the book was published in 1962 a ban on the use of DDT in the US occurred. But Carson also described many cases where the spraying of other chemicals greatly altered ecosystems in a negative manner. Did any of her research include examples involving wetlands environments created by the keystone species, the beaver? Yes – she found one such example in the writings of Supreme Court Justice, William O. Douglas.

Following the spraying of herbicide by the US Forest Service to some 10,000 acres of sage lands of the Bridger National Forest in Wyoming, Douglas recorded his observations of the resulting environmental damage. The herbicide was meant to kill the sage so that it could be replaced with grasses desired for cattle grazing within the area. Carson suggests that replacement of the sagebrush with species of grasses not adapted to the dry, harsh conditions of the area likely would not have resulted in a lush grassland that was expected. She writes about the unintended results this action had in the lines below from Silent Spring.1

“The sage was killed, as intended. But so was the green, lifegiving ribbon of willows that traced its way across these plains, following the meandering streams. Moose had lived in these willow thickets, for willow is to the moose what sage is to the antelope. Beaver had lived there, too, feeding on the willows, felling them and making a strong dam across the tiny stream. Through the labor of the beavers, a lake backed up. Trout in the mountain streams seldom were more than six inches long; in the lake they thrived so prodigiously that many grew to five pounds. Waterfowl were attracted to the lake, also. Merely because of the presence of the willows and the beavers that depended on them, the region was an attractive recreational area with excellent fishing and hunting.

But with the ‘improvement’ instituted by the Forest Service, the willows went the way of the sagebrush, killed by the same impartial spray. When Justice Douglas visited the area in 1959, the year of the spraying, he was shocked to see the shriveled and dying willows— the ‘vast, incredible damage’. What would become of the moose? Of the beavers and the little world they had constructed? A year later he returned to read the answers in the devastated landscape. The moose were gone and so were the beaver. Their principal dam had gone out for want of attention by its skilled architects, and the lake had drained away. None of the large trout were left. None could live in the tiny creek that remained, threading its way through a bare, hot land where no shade remained. The living world was shattered.”

Both then & now, the willow and the beaver together support a diverse community of flora and fauna such that removing one of them reduces the entire ecosystem of life. Beavers, with their water-retaining dam activity, are well known as a keystone species. An argument for the willow as a keystone species has also been made by science more recently. Research has shown that just a few keystone plant genera support the majority of Lepidoptera species (an order of insects that includes butterflies and moths).2 Two of the top 5 genera that were identified as keystone plants are Salix (the Willows group) & Populus (Poplars, Aspens, and Cottonwoods). Plants from these two groups tend to be the preferred food of the beaver so it might not be a surprise that two keystones in an ecosystem support many species.

Why are the butterflies & moths that feed on willows important? – they are a high nutritional food item for many species and are necessary to nesting birds’ success in raising their offspring.3

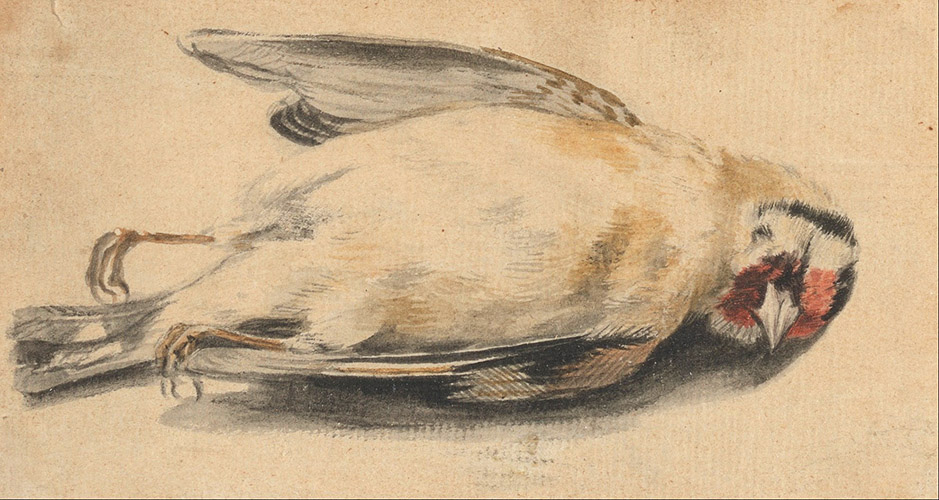

Birds are still in trouble today despite the warning message that Silent Spring sent out. A Scientific American article about our progress in protecting birds since Carson’s day cited a 2019 study that shows that 29 percent of North American birds have vanished since 1970. However, the study also showed that there was an increase of bird abundance by 13 percent in wetlands.4 Protecting wetlands and their keystone players does have positive effects on bird populations.

If we follow Carson’s thinking in terms of the web of connections among species before taking actions that affect the environment, perhaps our choices can minimize damage to all species (including humans) while maximizing ecosystem resilience. Recognizing the keystone roles of a few species is important in considering how balanced ecosystems function. Silent Spring not only marks an important moment in the history of environment awareness but also continues to be worthy of our attention today.

Concentrations of DDT in an estuary on the South Shore of Long Island, 1968

References

- Carson, R. “Chapter 6, Earth’s Green Mantle.” Silent Spring, A Mariner Books, Boston, 2002.

- Narango, D.L., Tallamy, D.W. & Shropshire, K.J. Few keystone plant genera support the majority of Lepidoptera species. Nat Commun 11, 5751 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19565-4

- Tallamy, Douglas W. Nature’s Best Hope a New Approach to Conservation That Starts in Your Yard. Timber Press, 2020.

- Oreskes, Naomi. “60 Years after Silent Spring Warned Us, Birds-and Humanity-Are Still in Trouble.” Scientific American, 1 Apr. 2022, www.scientificamerican.com/article/60-years-after-silent-spring-warned-us-birds-and-humanity-are-still-in-trouble/.